The Man behind Thangka Painting in Nepal

Before meeting an experienced and prominent Thangka painter of Nepal, our friend Yanik who had readily slipped into the role of the gatekeeper that day told me that somebody is going to translate things the artist we were going to meet would say. I dreaded thinking about it. ‘Now that sounds like playing Chinese Whisper,’ I snapped back. We walked ahead in silence till we reached one of the many blue gates to let ourselves be welcomed by his daughter-in-law to his abode in the inner residential area of Boudha.

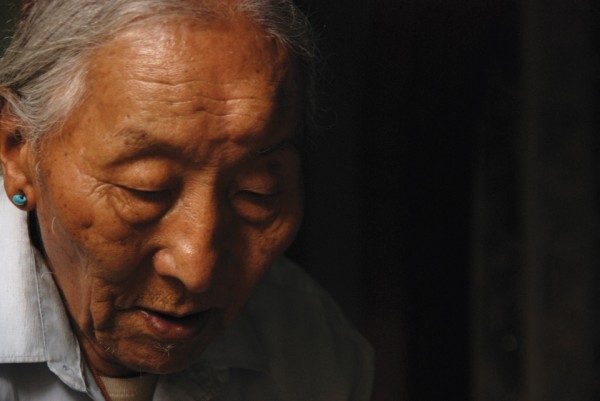

Sitting on the lounge bed in the living room in his house, he was silently waiting for us. We exchanged greetings waving our hands not knowing what to say exactly in Tibetan. So we greeted each other with Namaste. As I went closer to sit next to him, he said something which I could neither hear properly nor understand what he wanted to tell. I heard him say ’81’ and his daughter-in-law added right there in time ‘age’. How did I not get this? He was as though a child trying to introduce himself to us that he is a man of 81 years. Wow! It got me hard when I saw in him both the eagerness of a child and creases of an old man, and knew in an instance that he had experiences probably older than him to share.

Dharyyal Gngsur, who prefers to be called by his first name ‘Dharyyal’ is probably the biggest and reputed name in the field of Thangka painting in Nepal. Although at this age he has already retired to spiritual living and home-stay, he has however not

stopped painting Thangka. Given the good condition of his health which is rare these days he wouldn’t mind sitting down to make diagrams of Gods and Goddesses on the canvases so that his pupils could easily apply colours on them.

Born in an affluent artistic family of Thangka artists, his life took a different turn as his country did in 1950 with the invasion of China in Tibet. Dharyyal, who is the 6th generation Thangka painter of his family, is a witness who carries the legacy of the 7th generation Thangka artist— his son Wangdi with him. His son is not just a witness to the legacy but his family along with others had been left back in Tibet before fleeing to Nepal, in a search for a hideout from Chinese who confiscated

invaluable properties and jewelries and were only left

with rags. He further lamented that many of his contemporaries and friends had to end up in jail because the Chinese thought they were rich people and were hiding their precious jewels.

This could not go on for long. Tired of living a life of the oppressed, and the constant fear of Chinese who would ‘beat us, lock up us in jail even if we wore something little nice’ compelled him and others to leave the country for better. Before escaping to Nepal in 1964, he had already served for three years in jail in the Eastern part of Tibet. By then he already had a family of his own and was the father of four sons and a daughter. But, it was out of question to even think that he could escape to Nepal with his family members. And, because of religious and other matters like home and land, his family remained there while he silently fled, leaving back his family and country behind to an unknown land.

By then, he was already a good Thangka painter. But due to political upheavals his country had to go through, he was not able to practice it as his fathers and grandfathers did in their time. Unlike the many Tibetans who fled their home for safety and good life, they were not able to accomplish as Dharyyal could. As a child, he was taught the craft of Thangka painting by his father and grandfather who were all successful painters of their time. It took him time to practice his skills in the new place.

Before reaching anywhere in a safer place, he along with others had to cross the treacherous mountains for seven long days and nights almost without food to reach Solukhumbu. Solukhumbu was the resting point for most of the Tibetans as it provided many resemblances of their home culturally, religiously and geographically.

He decided to live there for some time and wait and see what would happen to his country because he had his family members waiting for him there. But nothing really changed. And, it didn’t take long for seven years to pass by as he stayed there looking for food and home. ‘I used to paint Thangka in the monasteries there and fill my hungry stomach,’ said the revered artist in a childlike manner without any inhibition.

This was the time when he could actually paint Thangka in the monasteries and exhibit his artistic skills to the people around and get work to do and earn his living. The people he met, made friends with and worked with knew his true potential of an artist which would take him to greater heights in the future. It was also the time he earned praises not just for his artistic abilities but his measurements found in ample amount in his work which was rare in others arts. ‘Measurement is very important to Thangka painting because it determines the beauty of Thangka art,’ shared Dharyyal, ‘every image of Gods and Goddesses have their measurements that tell good posture from a bad one.’

So, measurements and lines are what that helped him stand out from the rest in the time when struggles were what everybody was doing. After spending seven years of his life in Solukhumbu he moved towards the valley only to settle down here for the rest of his life. Around 1971/72 he entered the valley and felt a breath of new breeze breezing in the city. He knew he could do many things here through Thangka painting. Given his contacts and people he knew, he soon started working with Lamas of various monasteries in Kathmandu and built stronger bonds with them to work forever here. But, things didn’t go as he expected. His family members were still in Tibet while he was here alone working for and only for himself with no one to look forward to in the times of happiness and sadness. This was not what he wanted, but there was no choice than to resist the hard life.

Unable to live away from his family for a long time, in 1980, he mustered up enough courage to go to Tibet to be with his children and wife. He did for some time. But what little hope he had of his country and himself faded away with the time, and it was still not a safe place for him to be there. So, this time he had to run away, leaving back his family once again to Kathmandu where he had a different life waiting for him. The only difference this time was that his third youngest son was with him. He took his son Wangdi with him giving an excuse to the rest of their family that he was only taking him for a vacation. He would come back with his son after a few months. But, this never happened. They have ever since been living in Kathmandu.

Wangdi has a family of his own and it is his wife Tsering Chokey who translated the things being said by her in-law, Dharyyal. Wangdi does thangka painting and also runs a Thangka painting school opened by his father in the late 1970s. The school was opened with the intention of helping empower the youths in those days so they could earn their living out of Thangka painting. Dharyyal who then got busy with paintings of thangkas in the monasteries started getting more contracts to beautify the walls of monasteries that had slowly started to grow in those days. As a result, Dharyyal in capital has Sichen Gumba, White Monastery, Thangdu Gumba, Tusal Gumba, Swoyambhu Gumba, Kapan Monastery and Tamang Gumba to his credit. Likewise, he also painted the walls of Tangboche Gumba, Namche Gumba and Solukhumbu Gumba in Solukhumbu with beautiful images of Gods and Goddesses. And, there are several in India which he can’t name all.

At present, he along with his other team members are researching the Thangka painting in Nepal to build a seven-storied monastery with all the images of Gods and Goddesses in Tibet to reestablish the Gumba in his village in Eastern Tibet which was destroyed by Chinese in the time of invasion. He shares heart-rending news that he would not go to Tibet for the project. Asked why, he lightly answered in a childlike manner that he just ‘cannot go’ flapping his hands in the air. But, his valued works of Thangka paintings will go there and embrace the walls of the monastery bringing the dilapidated state of the place into life once again, and the paintings would once again breathe his love for his country and his family even though he is far away from them all.