‘I am Yeti,’ read the bold blue and yellow words adorning the high brick wall opposite the Ambassador Hotel in Lazimpat. My heart fluttered as I scanned the words again.

‘I am Yeti.’

My mind similarly began to postulate endless possibilities; who was this, where had they come from, what was their intent, when did they do it, why this wall and were they really a yeti? Yes, street art does crazy things to your mind. The enigma, the thrill and the idea that someone, someone one will never know, is out there bringing to life works of art for the rest of the world to enjoy without anything in return; now there is a nice thought.

‘I am Yeti.’

It was new and fresh. It was neither a political slogan nor an advertorial poster or a poorly worded English sign to welcome tourists. It represented a perspective, a perspective of someone without an agenda, someone who wanted to have fun and above most someone who had a talent to share. It is palpable to say that I was excited.

Walking a little further on Lazimpat Road, my contented grin turned into a smile of elation as I made sense of the big black letters that now covered the entire wall facing west at the main intersection. The character painted at the end indicated it was different artist, the style and the message similarly diverging from the work of Yeti. I was to find out later that this was Mr. K.

‘scitilopodot.’

I read backwards. Ah, ‘to do politics.’ Picking up the pace my eyes scanned the wall faster than my legs could carry me.

‘Me not,’ ‘old,’ no read again, ‘told.’

‘Mmy,’ ok, think. ‘Yummy?’ No. ‘Dummy?’ It could not be. Yes! ‘Mummy.’

‘MUMMY TOLD ME NOT TO DO POLITICS.’

By this stage I was all but dancing in the street. Here I was thinking I would be in Nepal during one of the country’s most historic modern periods – that of the ratification of the new constitution. Instead, days after the Constituent Assembly announced yet another extension, I find myself on the cusp of the nations bourgeoning street art movement, amidst a new wave of talent that seeks not to imbue my brain with propaganda but simply and beautifully express ‘art everywhere for everyone.’

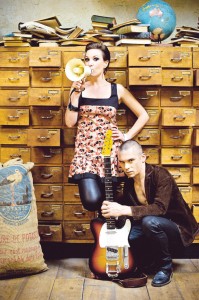

A week later I had to play it cool as I found myself in the company of Yeti, Bruno and Chandan. Together the trio are three of the six or so main players in this rebirth of street art in Nepal. Well, the lines are a little blurred as to whether this is a revival of a lost art or an awakening of a new era of artistic expression. In 2003 Sonik, a well known American artist, added some intricate murals to the Kathmandu cityscape. Then, a few years later when Bruno visited Nepal for the first time, he and Chandan ‘started doing a few tags around town.’ ‘I don’t know if we are the start of street art in Nepal but there are definitely more tags and murals than ever before,’ the mysterious Yeti explains. ‘We want street art in Nepal to grow. It is more enjoyable for the artists and the public if more people become involved. ..It really can make a city fun,’ adds Bruno, a photography student and artist from New York University.

And fun is what Kathmandu seems to need. After years of reading politically orientated slogans, being bombarded with movie posters and confronting ‘so many dirty and stained walls,’ residents are generally enthusiastic about waking to find a new mural as they begin their daily commute across the city. ‘If anything it makes the city look cleaner and more maintained,’ the quieter Chandan says as he enters the conversation. Of course street art can easily be, and often is, mistaken for graffiti, a term that generally carries negative connotations of dissident youth out to cause strife. ‘It’s not like that at all,’ Yeti elucidates, ‘we are respectful of private property and always ask permission before hand.’

Much of the work gracing the walls of Jamal, Lazimpat, Thamel and Pulchowk are, however, in prominent public spaces. Goods spots are those considered to be ‘smooth walls in a good location where lots of people can see it.’ Although, the group insist they are not trying to make any particular statement. ‘It’s about doing what we love and sharing it with the world,’ they collectively agree. ‘In the West, street art is a gate way to a professional art career,’ Bruno compares. ‘People take pictures, upload it to a website, gain a few advertisers, become more popular and then start selling their work for ridiculous amounts.’ Yeti extrapolates, ‘here it’s not about trying to make money. It is about passion and self satisfaction. When I put my work out there it is about sharing and hoping people like it.’

Unlike the rest of the world, street art in Nepal is not yet considered illegal. As the street art scene is just emerging, Bruno describes how ‘there have not been enough grounds for an anti-culture to emerge to counter and challenge the work we are doing. Most people are curious and just wonder what is going on.’ Pondering where sites of resistance may arise I suggest that in the West, at least, opposition to street art usually stems from an older, culturally traditional and politically conservative generation. Much to my surprise, Yeti chimes in that ‘old people have reacted positively when they see us paint, even offering words of encouragement.’ What about the police? ‘They don’t care either. One night they even helped us to clean a wall.’

I can’t get my head around it. ‘People generally wonder who would pay money to paint the city’s walls with art, with something that actually looks nice,’ Yeti clarifies. She continues to elaborate that ‘street art is new, it’s contemporary and it’s Western. When one cannot recognise something or see it for the first time they have a lot of questions.’ ‘Plus it comes down to diverging definitions of public space,’ Bruno helps me understand. ‘Everything in the West is a private space. Here public is public.’

Indeed it was curiosity from this art in distinct public spaces that had most of Kathmandu talking in early June as pockets of paintings sprang up around the city. Devoid of the convoluted and oft superfluous explanations normally found beside an artwork in a gallery, street artists’ capture their audiences’ imagination because one can interpret the work as they see it. For example, in the mural opposite the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, what I might perceive to be a social commentary of the all-consuming power of digital media, you may see, well, just a big pink monster. Street art, like life, is relative.

And it’s quite a process too. It begins with the planning of the location, drafting sketches and gathering the materials. On the creative process Yeti replies that ‘before you paint, you have a central idea, but your original sketch may change according to the space available.’ On the night they go out the group clean the wall for at least two hours before they begin paint. ‘You have to remove the dirt, the posters and make sure the space is as clean as possible before you start. If you skip this step it would probably turn out really shitty.’ A typical mural, which is normally several metres long and high, can take anywhere from three to five hours, to a couple of days. ‘It depends really on the size and how detailed the artwork is,’ Bruno describes. ‘Something like ‘I am Yeti’ will take a day and a half, ‘Money Never Sleeps’ took about 5 hours and Mr. K. usually works over a couple of nights.’

Usually an artist will have a particular character or trait that is unique to their work. This makes it possible for other artists and the public to identify who does what. But does that lead to competition? ‘It’s not a competition but if another artist is out overnight and you find it the next morning, you feel a drive,’ Yeti diplomatically responds. Bruno finishes her sentence adding that ‘it is not a drive to out-do one another, it’s a drive to improve yourself and become a better artist.’ ‘At the end of the day we like to paint and paint as much as we can,’ Yeti concludes. ‘After completing a mural at the end of a night we are all really dirty which makes for a good group hug.’

Group hugs, charm and talent. I think I am in love. With the art, with the movement and with the joy it can bring my day when I discover something new. Enigmatic, bold, colourful, different and fun. Yes, street art does crazy things to your mind.